How might we effectively teach computational thinking skills to children from low socioeconomic backgrounds?

Dekho Pakistan is a tangible game that introduces basic computational thinking skills to Pakistani government school children. The research was conducted to explore the language barrier while comparing digital and tangible versions of the game at government schools in Pakistan.

ROLE

UX Researcher

Designer

Developer

TOOLS & METHODS

User Interview

Field Studies

Usability Testing

Cultural Probes

Figma

Adobe Illustrator

HTML5/Javascript

TEAM

Tashfeen Ahmed

Rabiah Arshad

Abeera Riaz

DURATION

4 months

Concept

The concept behind Dekho Pakistan is to evaluate the retention of computational thinking (CT) and geographical knowledge while comparing the impact of learning in Urdu and English. The design is made keeping in mind the target audience, i.e. 10-12 years old kids with little to no prior knowledge about computers.

Design

The game was designed using well-known landmarks and cities of Pakistan. The objective of the game was to start at a particular landmark in a particular city and go through different landmarks and cities to reach the already known destination. Both tangible and digital versions of the game had Urdu and English variants.

Problem Statement

Pakistan produces about 445,000 university graduates and 10,000 computer science graduates per year. Despite these statistics, Pakistan still has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world and the second largest out of school population (5.1 million children) after Nigeria.

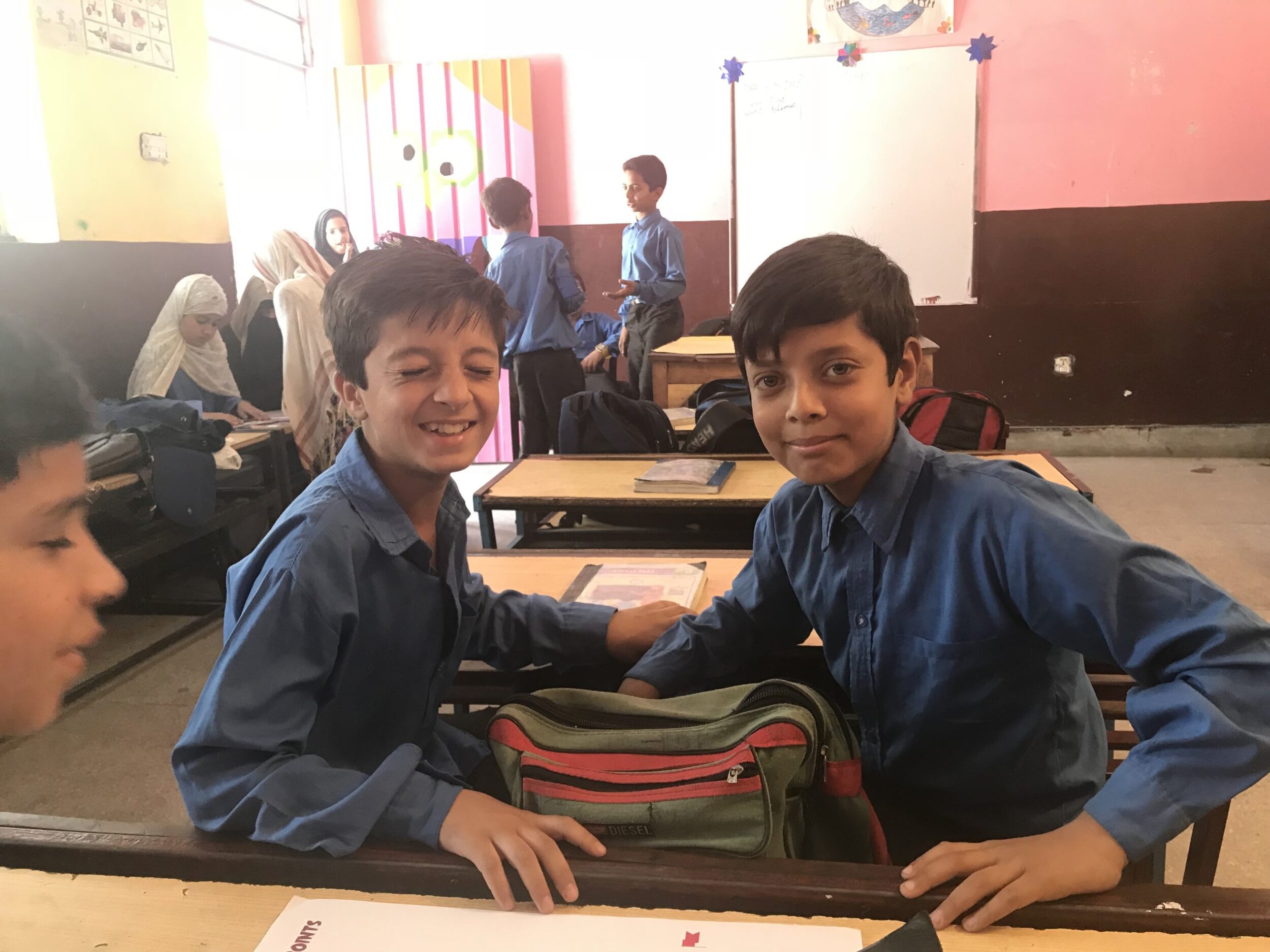

From initial interviews with students from primary and secondary schools, it was found that besides poor physical facilities and directionless education there exists a disconnect between the primary and secondary school curriculum. The aim of this project was to devise a fun and interactive method to teach computational thinking to children from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

My Role

My role mainly revolved around user research, game design and project management. I was part of all the field work conducted in government schools in Lahore and Kasur.

The Solution

A board game that challenges children, ages 10-12, to orient tangible, magnetized manipulatives to complete or create paths. An informal study to investigate the effectiveness of the game in fostering children’s problem-solving capacity was introduced during collaborative gameplay. The results informed our instructional interaction design to better support the learning activities and help children hone the involved CT skills.

It was found that the tangible modality of instructional games motivates children to grow their understanding of CT skills in a focused and engaging way.

Research

The game featured three levels which taught procedural programming, shortest path algorithm, loops and conditionals. Each player had to lay down cards in a particular order to reach the destination and the time to complete each level was noted. Some of the participants were able to easily complete level 2 once they learnt how the first level worked. Others wanted to play the game again to get a higher score. This demonstrated the interest that the kids took in the game.

Results

Students playing in Urdu had a much better understanding of the game concepts as compared to students playing in English and were able to apply those concepts faster in the game. Moreover, they also found it easier to play and understand tangible board game as compared to the non-tangible computer-based game.

Reflection & Takeaways

The study found that due to the unfamiliarity of using computers, the tangible game is a more effective way to introduce computational thinking to children living in rural areas or coming from a low socioeconomic class. As the tangible game was a hands-on experience, children were able to pick up concepts a lot faster. Furthermore, children that played the Urdu version of the games were able to complete the levels faster as compared to the children that played the English version. This shows that a native language (or the one that students are more comfortable with) improves learning outcomes. Finally, through simple observations, we were able to discover parallels such as personality or gender and how they were affecting the outcomes. For example, boys showed quicker timings when performing the tasks, however girls were quicker in picking up concepts that were verbally taught before the game.